West Texas Treasure

Photography by Ross Hecox.

Photography by Ross Hecox.

AFTER SLIDING OPEN A METAL DRAWER, Billy Klapper reaches in and pulls out something wrapped inside a plastic shopping bag. He carefully unwraps it and holds up an old short-shanked bit.

Klapper’s workshop has dozens of bits hanging on its walls, including snaffles, correction bits and long-shanked curbs made by various craftsmen through the years. They share space with old rodeo photos, several sets of deer antlers, two dusty bullwhips and numerous spurs, including a rusty pair missing one rowel.

The bit from the drawer was hidden away for a reason. It’s the first one Klapper ever built.

“It was stolen from me 46 years ago,” Klapper says. “But last year I found it.”

During the Western Heritage Classic in Abilene, Texas, someone brought it to Klapper’s booth at the event’s bit and spur show, wondering if Klapper knew its maker, because it had no maker’s marks. Klapper immediately recognized his first creation, and he was able to trade a pair of collectible spurs he made for it.

Built in 1963, the bit has a floating spoon mouthpiece with a brass roller, and silver conchos on the cheekpieces hand-engraved and mounted by legendary craftsman Adolph Bayers. Bayers, who died in 1978, lived in Gilliland, Texas, and influenced Klapper as he transitioned from working cowboy to bit- and spurmaker. Bayers incorporated blacksmithing techniques and made spurs by hammering out one piece of steel — no welding. Klapper has done the same.

“Adolph Bayers was absolutely the greatest ever, in my opinion,” says collector and author J. Martin Basinger, who has written three books on Bayers. “Bill Klapper is right there with Adolph Bayers. There will be no more bit-and spurmakers like them. I know that’s a pretty big statement to make, but I’ve seen so many others who don’t use the same [blacksmithing] methods. I think Bill Klapper and Adolph Bayers are the end of really great spurmakers that just get a piece of steel and hammer it out, and turn out a great product.”

Bayers and Klapper also each built a loyal clientele of working cowboys.

“I think Bill Klapper and Adolph Bayers are the end of really great spurmakers that just get a piece of steel and hammer it out, and turn out a great product.” – J. Martin Basinger

“They have always been right in the middle of cowboy country,” says John Welch, who ranches in Colorado and Texas. “The thing that made their gear so usable is the fact that Billy, like Adolph before him, took a lot of input from cowboys.”

Many cutting horse trainers and competitors also use Klapper bits and spurs, claiming that their functionality is unmatched.

“To me he has a God-given gift of knowing exactly how to build a bit so that a horse has the right feel with it,” says Oklahoma rancher Shannon Hall, who has won nearly $3.3 million as a cutting horse trainer. “I’ve bought several copies of his bits, made by good bitmakers. They were beautiful and looked just like a Klapper. I mean, looked like they had imitated it perfectly. But you put it on a horse and it didn’t feel the same. I don’t know if it’s the metal he uses, the weight — I don’t know. I haven’t found one imitation yet that feels like a Klapper does.”

BILLY KLAPPER WAS 25 YEARS OLD when he built his first bit. Up until then, he had never considered taking up the craft. Born in 1937, he was raised in Lazare, a small community southeast of Childress, Texas. His father farmed and did mechanical work for neighbors. From a young age Klapper was interested in horses and the cowboy way of life.

“I was wanting a horse, and Daddy bought me a dang donkey. That’s what I was riding when I lost that rowel on those spurs,” Klapper says, pointing to the rusty pair hanging on his wall. The donkey liked to buck, opened gates, escaped its pasture and at times made itself a nuisance around town.

By the time Klapper was 11, he was running a tractor and doing farm work for a horse breeder who lived a few miles away. The man eventually bought Klapper his first horse, not long after Klapper sold his donkey to a cattleman who lived down the road.

After high school, Klapper began working cattle on local ranches, and then hired on full-time at the Buckle L near Childress. After two years, he moved on to the Y Ranch near Paducah. During a winter that had been unusually cold and snowy, Klapper had time to kill so he began working on his first bit.

“The foreman there had messed around some with making spurs,” Klapper recalls. “He was 73 when I went to work for him and had cataracts and had quit [building spurs], but he still had the tools and a forge. I had been wanting some bits, but Bayers was so far behind that you couldn’t hardly get anything. The foreman said, ‘You can make what you want in that old shop.’ I said, ‘I can’t make that.’ But when it came up a big snow that winter, that’s when I started.”

The design was far from simple, with swivel shanks, a floating spoon and a roller. And though it took weeks to complete, the finished product was a working bit that Klapper used as a cowboy for years.

“That bit shows you what kind of talent that this man has,” Basinger says.

Klapper paid Bayers to put silver on his bit, and then the master craftsman showed him how to mount silver on another bit he’d made. Soon, Klapper started building bits for cowboys he knew, often working until 11 o’clock at night. In 1965, Klapper began working for a ranch located just a few miles away from Bayers’ shop in Gilliland, about 90 miles west of Wichita Falls, Texas. Klapper visited the shop several times, but he was always careful not to trouble Bayers with questions about building bits and spurs. Bayers wasn’t one to share all of his expertise.

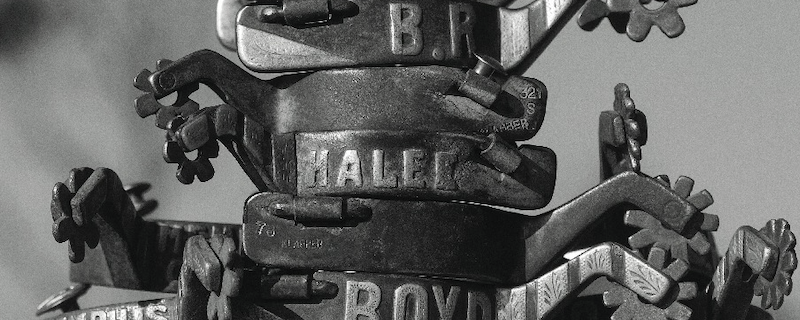

Klapper still builds spurs out of one piece of metal. Photography by Ross Hecox.

Klapper still builds spurs out of one piece of metal. Photography by Ross Hecox.

“The first time I went down there, I wasn’t there very long when a guy came by and wanted to learn, and Bayers said, ‘I’m not running a school,’ ” Klapper recalls. “So I kept my mouth shut. I didn’t want him mad at me.”

One day, a cowboy asked Klapper to build a pair of spurs, but he has never made any.

“I told him I’d make myself a pair, and if they came out all right I’d make him a pair,” he says. “I’d been visiting Adolph. I never would ask him questions about spurs. I just caught him at different stages in his spur-making. While I was talking, I was studying that spur in the same time.”

The process involved cutting about 5 inches of an axle rod from an old Ford vehicle manufactured before 1949 (the grade of steel Ford used was changed after that, and metal used in Chevrolets was too hard), and then making a length-wise, 3-inch cut down the center of the rod. Using a forge, hammer and anvil, the cut was widened, and the two split sides shaped into heel bands. The uncut portion became the shank. A machine called a trip hammer handled the heavy work of shaping the steel, saving the blacksmith’s arm and shoulders.

Nowadays, pre-1949 Ford axles are hard to find, but Klapper still starts with one length of steel and shapes it into spurs.

While he was still cowboying, Klapper began building saddle D-rings for Windy Ryon’s saddle shop in Fort Worth (Bayers had grown tired of the job and gladly showed Klapper how to perform that monotonous task), and then Klapper began making spurs for the iconic businessman, earning $20 a pair. Ryon sold them in his store for $45.

By 1968, Klapper had a wife, two little girls, and a big decision to make.

“It got to a point that I had so many orders, I was going to have to quit [making bits and spurs] or quit cowboying, either one,” he says. “I may have to work a little harder at this, but I thought I could make more money and stay warm in the wintertime. I liked to cowboy, but there’s no money in it, and I had a family. It’s just living from one paycheck to another.”

Klapper set up shop near Childress before relocating to Pampa in 1973. When he started, he could build one pair of spurs in a day.

“That wasn’t no 8-hour day, either,” he says. “I’d be at work at 5 o’clock in the morning, and it would take until 10 or 11 at night to get done.”

CAROL ROSE VIVIDLY REMEMBERS meeting Billy Klapper for the first time. At the time, the American Quarter Horse Association Hall of Fame breeder was married to Matlock Rose, who had won the 1967 National Cutting Horse Association Open World Championship on Peppy San and was well on his way to a hall of fame career as a trainer. Windy Ryon had given Matlock and Carol each a pair of Klapper spurs as wedding gifts in 1968. A year or two later, Matlock took her to Childress to meet Klapper.

“I don’t keep my Klapper bridles at the barn. I keep them locked in a safe. They’re too valuable.” – Shannon Hall

“We walk into this tin building, and it was as cold as it possibly could be,” Carol says. “Billy Klapper was the only one in there, a cowboy-looking guy, very short with words, chewing tobacco in his mouth. I shook his hand, and he had the most friendly eyes. We became instant friends.

“Matlock was talking to him, and looking around I was just flabbergasted. There wasn’t much equipment, there was a big work bench, and this man by himself was making the most beautiful bits and spurs.”

In 1969, Matlock ordered his first Klapper bit, mailing a specific design for Klapper to build. With an elegant, snake-like curve in its 6 1/2-inch shanks and a solid, high-ported mouthpiece, the “27” became one of Klapper’s most popular bits. Many of them had five to seven silver bars along the shank with a simple wheat pattern engraved on them. It didn’t hurt that one of the most successful trainers was winning cutting horse events with it.

“The first [Klapper] bit I ordered was a 27, because all I ever heard was, ‘You’ve got to have a 27,’ ” Hall says.

“His number 27 bit, everyone has tried to copy it, and nobody has ever got it right,” adds Basinger.

Legendary Arizona horseman Don Dodge also ordered a 27, but later requested a lighter bit. So Klapper made a thinner mouthpiece and attached it to the shanks of a 27. The result was the “299. “

“I told Don that if it didn’t work, he didn’t own it,” Klapper says. “But it really worked good.”

Klapper has 897 bit patterns and 782 spur designs. All of the patterns are drawn in a collection of spiral notebooks that sit in a metal desk drawer in his shop. He says he has no idea how many thousands of orders he has filled over the past five decades.

The Klapper 27, this one owned by Shannon Hall, has been Klapper’s most popular bit. Photography by Ross Hecox.

The Klapper 27, this one owned by Shannon Hall, has been Klapper’s most popular bit. Photography by Ross Hecox.

He credits Matlock Rose for opening up a new market for him, and since then he has also built bits and spurs for barrel racers, ropers and other horsemen. The high demand for his work has increased its value considerably. His price for a pair of spurs or a bit starts at a little above $2,100. Collectors and dealers often ask for somewhere around $3,000.

Unfortunately, the high value of Klapper gear makes it susceptible to theft.

“I don’t keep my Klapper bridles at the barn,” Hall says. “I keep them locked in a safe. They’re too valuable. When I was showing a lot, I always carried my Klapper bit with me. I never left it at the stalls, never left it in the truck. It always went to the motel with me. I’d get in an elevator in a motel and city people would say, ‘Son, you lost your horse.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, I didn’t care about him. But I got my bridle.’ “

Horsemen like Hall and cutting trainer Kory Pounds agree that Klapper bits and spurs aren’t in high demand simply because of the name stamped on their mouthpiece or heel band.

“There isn’t any hype behind his gear,” Pounds says. “It has lived up to its reputation.”

“Some of his bits are pretty long shanked, but the mouthpieces on most of them are not real severe on a horse,” Welch adds. “You get instant contact with them. They immediately begin to have an effect, but they don’t have a real abrupt, severe kind of effect. That’s what I like about them.”

Many horsemen say Klapper bits consistently work well with nearly any horse.

“No doubt about it,” says Texas cutting and cow horse trainer Boyd Rice. “I don’t know what the difference is [from other bits], but they do feel better. Bayers bits are the same way. I don’t know if it’s the metal or what. They just work.”

Bit- and spurmaker Stewart Williamson agrees there is a mystery to how Klapper bits function.

“I was talking to [fellow craftsman] Wilson Capron about another maker, and how good his spurs felt,” Williamson says. “And Wilson said, ‘Maybe you’re feeling the heart that went into that project.’ I kind of shrugged it off. But now that I’ve done this work for a few years, I’ve found that the more time you put into these projects, something [intangible] does go into them.

“I think Billy really prefers to make bits and spurs for people that are going to use them, versus those that are wanting to trade them.” – John Welch

“Billy is starting from raw stock, so he is hands-on through the whole process. Who’s to say that he can’t put ‘something’ into it? I know that sounds mystical and weird, but I’m not going to discount it.”

SHANNON HALL’S FATHER, Donnie, cowboyed his entire life and consequently didn’t have much material wealth to pass down to his children. However, he was able to give them his most treasured gear.

“My only inheritance from my dad is a pair of gal-leg spurs made by Billy Klapper,” Hall says. “Dad was proud to give those to me.

“When each of my three girls were born, I had a pair of Klapper spurs with their names made for each of them. I bought them diapers and clothes first, but the next thing was a set of Klapper spurs.”

Likewise, Welch and his wife gave each of their three sons a pair of Klapper spurs for Christmas one year. Carol Rose has given Klapper spurs to many friends, family and loyal employees.

John Means, a rancher from Valentine, Texas, has bought Klapper spurs for his wife, three children, their spouses, and two of his three grandchildren (the newborn grandbaby should be receiving a pair soon).

Cutting and cow horse trainer Boyd Rice and his wife, Halee, have ridden with Klapper spurs for many years. Photography by Ross Hecox.

Cutting and cow horse trainer Boyd Rice and his wife, Halee, have ridden with Klapper spurs for many years. Photography by Ross Hecox.

“You can just put a pair of his spurs in your hand and they feel good,” Means says. “They sit good on your boot. They have nice balance and weight.

“We’re ranch people, so we use them. That’s all I use is one pair of his spurs with the rowels worn out. He respects cowboys and he understands them.

“But beyond that, Billy is just a class act. We hunt with him and have a great time just visiting. My friendship with him is paramount.”

Basinger has set up a booth next to Klapper several times at the Western Heritage Classic, and he says the now 81-year-old craftsman draws a crowd of people, many of them bit and spur collectors who admire his work.

“He’s covered up with people there,” Basinger says. “And he’s gotten a reputation as being kind of grumpy. He’s not. It’s just that he’s had people after him all the time to build them something.

“One year there was a young couple that wanted to talk to Bill at Abilene, but they couldn’t get in there. They didn’t want to just push into his booth like everybody else was, so they’d stay there awhile, and then come back later. But they just couldn’t get in to talk to him. Bill had noticed them. Finally, they came back again and he made a point to talk to them, and he spent all the time they needed. They probably didn’t have much money to buy a pair of Klapper spurs, but I’ll guarantee you that those folks didn’t wait very long for those spurs. That’s the kind of guy Bill Klapper is. Those people were his kind of folks.”

Welch adds that building collectibles or gallery pieces never appealed to Klapper.

“I think Billy really prefers to make bits and spurs for people that are going to use them, versus those that are wanting to trade them,” Welch says.

Klapper holds one of his bits, which features a classic silver design. Photography by Ross Hecox.

Klapper holds one of his bits, which features a classic silver design. Photography by Ross Hecox.

Welch, Rose, Means, Hall and Basinger have all used their Klapper bits and spurs, and their appreciation for the gear he custom-made for them goes beyond monetary value, craftsmanship or functionality. There are horse stories, fond memories, and important lessons attached to their bits and spurs, and they also represent a connection to a man they know and admire.

Back in his shop in Pampa, Klapper returns his original bit to its hiding place. It’s funny to think that, in a way, a bit without his maker’s mark might be the most valuable Klapper bit of all.

This article was originally published in the May 2018 issue of Western Horseman.

The post West Texas Treasure appeared first on Western Horseman.

Mashups and APIs

- Home

- About Us

- Write For Us / Submit Content

- Advertising And Affiliates

- Feeds And Syndication

- Contact Us

- Login

- Privacy

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.